Hobbes' concept of the natural state of man. Thomas Hobbes' doctrine of state and law

The Science of Civil Society by T. Hobbes

English philosopher and political theorist Thomas Hobbes, who made the first conscious attempt to build the “science” of Civil Society on the basis of primary principles arising from the idea of what Man would be in a state in which all power - political, moral and social - would be absent. According to his theory, society is like man - its simplest

element, there is a car. To understand how it works, you need

imagine it separately, decompose it into its simplest elements and then rebuild it

fold according to the laws of motion of components. Hobbes distinguished

artificial "(made by Man) and natural (formed

physically) world. A person can only have certain knowledge about

what people have created. In them he sought to show that the natural state of Man, in which all power was absent and in which he enjoyed a natural right to everything that helped his self-preservation, was an endless struggle, for the protection of his aspirations was not ensured. Because Man had a mind that enabled him to know the causes of things, he was able to discover those principles of conduct which he must prudently follow for his own safety.

It was upon these principles, called by Hobbes the "convenient clauses of the world," that men agreed to establish their natural right to all things, and to submit to an absolute sovereign power.

Hobbes's conclusions point to monarchical rule, but he was always careful when addressing this topic, using the phrase "one man or a congregation of men." In those days it was dangerous to touch royalist and parliamentary sore points.

Thomas Hobbes' Doctrine of Man

If we try to characterize the internal logic of philosophical

Hobbes's research, the following picture emerges.

The problem of power, the problem of genesis and essence state hostel was one of the central philosophical and sociological problems facing progressive thinkers of the 16th - 17th centuries during the era of creation nation states in Europe, strengthening their sovereignty and forming state institutions. In England, during the revolution and civil war, this problem was especially acute. It is not surprising that the development of issues of moral and civil philosophy, or the philosophy of the state, primarily attracted Hobbes' attention. The philosopher himself emphasized this in the dedication preceding the work “On the Body,” in which he defines his place among other founders of science and philosophy of modern times.

The development of these questions forced Hobbes to turn to the study of man. The English philosopher, like many other progressive thinkers of that era, who did not rise to the level of understanding real, material causes social development, tried to explain the essence of social life based on the principles of “Human Nature”. In contrast to Aristotle's principle, which states that man is a social being, Hobbes argues that man is not social by nature. In fact, if a person loved another only as a person, why should he not love everyone equally? In society we are not looking for friends, but for the fulfillment of our own interests.

“What do all people do that they consider pleasure, if not slander and arrogance? Everyone wants to play the first role and oppress others; everyone claims talent and knowledge, and as many listeners in the audience as there are doctors. Everyone strives not for cohabitation with others, but for power over them and, therefore, for war. War of all against all is still the law of savages, and the state of war is still a natural law in relations between states and between rulers,” writes Hobbes. According to Hobbes, our experience, the facts of everyday life, tell us that there is distrust between people “When a man goes on a journey, a man takes with him a weapon and takes with him a large company; when he goes to bed, he locks the door; We drive around armed, since we lock our doors, about our children and about our servants, since we lock our boxes? Don’t we blame people with these actions just as I blame them with my statements?”

However, Hobbes adds, none of us can blame them. The desires and passions of people are not sinful. And when people live in natural state, no unjust acts can exist. The concept of good and evil can exist where society and laws exist; where there are no established ones, there can be no injustice. Justice and injustice, according to Hobbes, are not faculties of either soul or body. For if they were such, a person would own them, even being alone in the world, just as he owns perception and feeling. Justice and injustice are the qualities and properties of a person living not alone, but in society. But what pushes people to live together in peace among themselves, contrary to their inclinations, to mutual struggle and to mutual destruction. Where

look for the rules and concepts on which human society is based?

According to Hobbes, such a rule becomes a natural law based on reason, with the help of which everyone ascribes to himself abstinence from everything that, in his opinion, may be harmful to him.

The first fundamental law of nature is that every one must seek peace by every means at his disposal, and if he cannot obtain peace, he may seek and use all the means and advantages of war. From this law follows directly the second law: everyone must be willing to renounce his right to everything when others also desire it, since he considers this renunciation necessary for peace and self-defense. In addition to waiving your rights, there may also be a transfer of these rights. When two or more people transfer these rights to each other, it is called a contract. The third natural law states that people must keep their own contracts. This law contains the function of justice. Only with the transfer of rights does community life and the functioning of property begin, and only then is injustice possible in the violation of contracts. It is extremely interesting that Hobbes derives from these fundamental laws the law of Christian morality: “Do not do to others what you would not have done to you.” According to Hobbes, natural laws, being the rules of our reason, are eternal. The name "law" is not quite suitable for them, but since they are considered as the command of God, they are "laws".

Pre-state (natural) state, the emergence of the state and the status of state sovereignty according to T. Hobbes

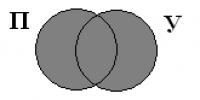

The source of the doctrine of law and state is the doctrine of the pre-state (natural) state - this is the state in which society exists before the state. According to Hobbes, the pre-state state is formed by natural rights. That is, every person, in interaction with others, freely exercises natural rights. To get out of the natural state, people create a state.

The source of the state is a social contract, the essence of which is the voluntary transfer by members of society of their natural rights to a person or group of persons who acquire power.

According to Hobbes, the state is the only object of power and the absolute sovereign.

Unlike Machiavelli, Hobbes' theory of statism is based on the concept of natural law.

Hobbes distinguishes between the pre-state, i.e. natural, state (status naturalis) and state, i.e. civil, status (status civilis).

In the state of nature, man acts as a physical body and is governed by natural law (jus naturale). Natural law is “the freedom of every man to exercise his own strength at its own discretion to preserve its own nature, i.e. own life, and, consequently, freedom to do whatever in his own judgment and understanding is the most suitable means for doing it.”

The state of nature is a state of war of all against all (bellum omnium contra omnes); a state of constant fear for one's life.

However, people have a natural mind, which instructs them to follow natural laws (leges naturalis) - unchanging and eternal. Natural law (lex naturalis) - “found by reason general rule, according to which a person is prohibited from doing what is detrimental to his life or which deprives him of the means of preserving it, and from missing out on what he considers the best means of preserving life.”

Hobbes distinguishes three fundamental natural laws.

1. Law as a goal: “one should seek peace and follow

2. Law as a means: “if others agree

people must agree to give up the right to all things

to the extent necessary in the interests of peace and security

protection, and be content with this degree of freedom according to

attitude towards other people, which he would allow in others

other people towards themselves." Give up the right to

all things means for Hobbes “to abolish community and

society" and establish ownership, absence of co

which in its natural state is the cause of the “war of all”

Against everyone".

3. Law as a duty: “people must fulfill the concluded

agreements made by them, without which the agreements have no meaning

who cares" (pacta sunt servanda).

Hobbes is a materialist. He believed that man is a body in the world of bodies: “Man is not only a physical body; it is also part of the state, in other words, part of the body politic. And for this reason he should be considered equally as a man and as a citizen."

Hobbes identifies three forms of government:

Monarchy;

Aristocracy;

Democracy.

Monarchy is a form of government in which general interests coincide most of all with private interests: “The wealth, power and glory of the monarch are determined by the wealth, power and glory of his subjects.”

Aristocracy is a form of government in which “supreme power belongs to an assembly of only a part of the citizens.”

Democracy is a form of government in which the supreme power belongs to the assembly of all.

Hobbes criticized monarchy because the inheritance of supreme power can go to a minor or to someone who cannot distinguish between good and evil. But democracy also attracted his criticism, since in relation to deciding questions of war and peace and in relation to drawing up laws, it finds itself in “the same position as if the supreme power were in the hands of a minor.”

The image of the state. The state appears to Hobbes as Leviathan. Leviathan is a sea monster reported in the Bible. Leviathan's body is covered with scales, each of which symbolizes a citizen of the state, and in his hands there are symbols state power: “For by art was created that great Leviathan, which is called the state (in Latin civitas) and which is only artificial person, though larger in size and stronger than the natural man for whose protection and protection he was created.”

Hobbes draws analogies between the state as an artificial person and man as such: the supreme power is the soul; magistrates - joints; reward and punishment - nerves; the welfare and wealth of individuals is power; the safety of the people is an occupation; justice and laws - artificial intelligence and will; civil peace - health; turmoil - illness; civil war is death.

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) interpreted the problem of the relationship between law and law from a clearly expressed statist (statist) position. Significant importance in the development of this topic, as in the entire political and legal teaching of Hobbes, is attached to the fundamental opposition of the state of nature to the state (civil state).

Hobbes proceeds from the fact that “nature created men equal in physical and mental abilities” 5c. In any case, the possible natural difference between people is not so great that one of them could claim for himself some good that the other could not claim with the same right.

58 Hobbes T. Leviathan or matter, form and power of the state, ecclesiastical and civil. M., 1936, p. 113. In the following, for the sake of brevity, this work will be referred to as “Leviathan.” See also: Hobbes T. Philosophical foundations of the doctrine of the citizen. M., 1914, p. 22 et seq.

Such equality of people, meaning their equal opportunities to harm each other, combined with the three main causes of war rooted in human nature (competition, mistrust, love of glory) leads, according to Hobbes, to the fact that the state of nature turns out to be a general, unceasing war.. " From here it is obvious,” he writes, “that as long as people live without a common power that keeps them all in fear, they are in that state called war, and precisely in a state of war of all against all.”59

In Hobbes's depiction of the state of nature, there is no general authority. And where there is no general power, he notes, there is no law, and where there is no law, there is no justice. There is also no property, no possession, no distinction between mine and yours. Everyone in the state of nature has the right to everything - this is his natural right and natural freedom.

Hobbes defines natural law as follows: “Natural right, commonly called jus naturale by writers, is the liberty of every man to use his own powers as he pleases, for the preservation of his own nature, that is, his own life, and therefore the liberty of doing all that which, in his own judgment and understanding, is the most suitable means for this purpose” eo.

Freedom in his teaching means the absence of external obstacles to do what a person wants, since he is able to do it according to his physical abilities. In this sense, man, according to Hobbes, is free precisely in the state of nature.

Natural law, according to Hobbes, should not be confused with natural law (lex naturalis) - a prescription or found by reason general rule, according to which a person is prohibited from doing something that is detrimental to his life or that deprives him of the means to preserve it, and to miss what he considers the best means to preserve life.

Hobbes emphasizes: “It is necessary to distinguish between jus and lex, between right and law, although those who write on this subject usually confuse these concepts: for right consists in the freedom to do or not to do, while

™ Hobbes T. Leviathan, p. 115. 60 Ibid., p. 117.

how the law determines and obliges one or another member of this alternative, so that law and right differ from each other in the same way as obligation and freedom, which are incompatible in relation to the same thing."

Man is a rational being, and the general rule and injunction of reason, according to Hobbes, sounds like this: “... every man should strive for peace, since he has the hope of achieving it, but if he cannot achieve it, then he can use any means that give an advantage in war” e2.

This prescription of reason, testifying to Hobbes’s peculiar rationalistic (appealing to reason) approach to the topic under discussion, contains both rules of behavior in the state of nature (in the second part of the above form we're talking about about natural law sanctioned by reason), and the rule for emerging from the natural state of general war to peace (the first part of the formula). The first part of Hobbes's maxim of reason appears as the first and fundamental natural law: peace should be sought and followed.

From this basic natural law, Hobbes, resorting to deduction, derives a whole series of other natural laws that specify the rule for searching for civil peace between people63.

Thus, the second natural law states that if other people consent to it, a person must agree to renounce the right to all things to the extent necessary in the interests of peace and self-defense, and to be content with such a degree of freedom in relation to other people as he would allow other people to treat him. Hobbes notes that the requirement of this law is already presented in the well-known gospel formula: act towards others as you would like others to act towards you.

In another formulation, which, according to Hobbes, summarizes the basic meaning of all natural laws, this rule states: do not do to others what you would not want them to do to you.

"Ibid. vg Ibid., p. U8.

63 See: Ibid., p. 118-138; It's him. Philosophical foundations of the doctrine of the citizen, p. 30-59.

8 V. S. Nersesyants 225

The Third Natural Law requires people to keep the agreements they make. This law, according to Hobbes, contains the source and beginning of justice. Injustice is failure to fulfill a contract, and everything that is not unfair is fair.

However, agreements based on trust are void where there is fear of non-fulfillment (i.e. in the state of nature). “That is why,” he writes, “before the words just and unjust can take place, there must be some kind of coercive power, which, by the threat of punishment outweighing the good expected by people from their violation of the agreement, would force people in equal measure to fulfill them agreements and would strengthen the property that people acquire through mutual agreements in return for the renunciation of universal rights. And such power can appear with the founding of a state” 64.

Hobbes interprets the widespread definition of justice as the unchanging will to give (reward) to everyone his own in the spirit of his concept: justice presupposes one’s own (property), and the latter is possible only where there is a state and coercive civil power.

The rest of the natural laws formulated by Hobbes require compliance with the rules of gratitude, gratitude, modesty, mercy, forgiveness, the inviolability of peace brokers, impartial and impartial resolution of disputes, etc.65

Natural laws are unchanging and eternal. “For,” Hobbes explains, “injustice, ingratitude, arrogance, pride, crookedness, partiality and other vices can never become legitimate, since it can never be that war preserves life and peace destroys it”6.

64 Hobbes T. Leviathan, p. 127.

85 One of the natural laws prohibits drunkenness and everything that deviates the mind from its natural state, thereby destroying or diminishing the power of reasoning. The basis for the formulation of this law is as follows: natural law is the command of right reason (recta ratio), and the latter in the state of nature is “an act of reasoning, i.e. each individual’s own and true reasoning about his actions, which can lead to benefit or harm for other people” (Hobbes T. Philosophical Foundations of the Doctrine of the Citizen, pp. 30, 53-54).

66 Hobbes T. Leviathan, p. 137.

He characterizes the science of natural laws as the only and true philosophy of morality, as the science of good and evil in human actions and in social life.

Hobbes notes the inaccuracy of applying the name law to the prescriptions of reason, which are the “natural laws” he formulates. “For,” he continues, “these precepts are only conclusions or theorems as to what leads to the preservation and protection human life, while law in its proper sense means the injunction of one who rightfully commands others. However, if we consider these very theorems as proclaimed by God, who commands everything with justice, then they are correctly called laws.”67

The presence of natural laws alone does not lead to peace and security. The observance of these laws can only be ensured by a common power that keeps people in fear and directs their actions towards the common good. Such a common power, according to Hobbes' contractual theory of the emergence of the state, can be established only by concentrating all power and all force in one person or collection of people, bringing all the wills of the parties to the contract into a single will. The multitude of people thus united in one person (the sovereign) is the state (civitas).

Describing the process of state formation, Hobbes writes: “Such is the birth of that great Leviathan, or rather (to speak more respectfully) of that mortal god, to whom we, under the dominion of an immortal god, owe our peace and our protection. For by virtue of the powers given to him by every individual in the state, the said person or assembly of persons enjoys such great concentrated power and authority in him that the fear inspired by that power and authority makes that person or that assembly of persons capable of directing the will of all men towards peace within and to mutual assistance against an external enemy. And in this person or assembly of persons consists the essence of the state, which can be defined as a single person, for whose actions a great many people have made themselves responsible by mutual agreement among themselves, so that this person can use the power and means of them all so,

There, p. 138.

as it deems necessary for their peace and common defense” 6\ The bearer of this person, the sovereign, has supreme power over his subjects. “Sovereign power,” Hobbes emphasizes, “is the soul of the state” 69.

Among the powers of the sovereign, Hobbes specifically highlights such rights as establishing laws, punishing lawbreakers, declaring war and making peace, administering justice, establishing a system of organs, prohibiting harmful teachings that lead to disruption of peace, etc. However, the powers of the sovereign are not limited to this, since the listed morals, according to Hobbes, imply other rights that are necessary to carry out the tasks of the state.

The supreme power in any form of state (democracy, aristocracy or monarchy) is, according to Hobbes, absolute in nature: it is “as extensive as can be imagined” 70.

Concerning the question of the duties of the sovereign, Hobbes observes: “The duties of the sovereign (whether monarch or assembly) are determined by the end for which he was invested with the supreme power, namely, the security of the people, to which he is obliged by natural law, and for which he is responsible to God, the creator of this law, and before no one else" 71.

Hobbes, at the same time, writes that “there are some rights that cannot be thought of, so that anyone can cede or alienate them by words or signs” 72. Among these inalienable (natural) rights of man, he names the right of resistance to those who encroach on his life and health, whoever wants to put him in chains or imprison him.

In general, Hobbes notes that “every subject has freedom in respect of everything the right to which cannot be alienated by contract”73. Thus, no contract can oblige a person to accuse himself and confess to the accusation, to kill or injure himself or another, to abstain from food, use

water and air, the use of medicines and other things necessary for life. A subject is free to disobey the sovereign's orders to perform such acts, so long as, Hobbes emphasizes, our refusal to obey in such cases does not undermine the purpose for which the sovereign power was established.

The remaining liberties of subjects "arise from the omissions of the law." 74 Where the sovereign has not prescribed any rules, the subject is free to do or not to do anything as he pleases. The measure and volume of such freedom of subjects in different states depend on the circumstances of place and time and are determined by the supreme power, its ideas about expediency, etc.

The inalienable rights of a subject, recognized by Hobbes, generally relate to issues of his personal self-preservation and self-defense. According to the Hobbesian concept, within these limits, a subject can resist civil authority. Therefore, the subsequent actions of the criminal, dictated by motives of self-defense (for example, armed resistance of rebels who face the death penalty; escape of a prisoner from prison or from the place of execution, etc.) are not a “new illegal act” 75.

But no one, Hobbes emphasizes, has the right to resist the “sword of the state” in order to protect another person (guilty or innocent), since such a right deprives the sovereign of the ability to protect the safety of his subjects and destroys the very essence of power.

About the laws issued by the sovereign, Hobbes writes: “These rules about property (or about mine and yours) and about good, evil, lawful and illegal in human actions are civil laws, that is, the special laws of each individual state...” 7b

He calls civil laws artificial chains for subjects, whose freedom consists only in what is passed over by the silence of the sovereign (legislator) when regulating the actions of people.

However, such freedom does not in any way abolish or limit the sovereign's power over life and death.

74 Ibid., p. 178.

76 Ibid., p. 151.

subjects. The only limitation on the sovereign is that, being himself a subject of God, he must obey natural laws. But if the sovereign violates them, thereby causing damage to his subjects, he, by. the meaning of the Hobbesian concept of sovereignty, he will only commit a sin before God, but not injustice towards his subjects.

In the civil state, we can actually talk only about the freedom of the state, and not of private individuals. The purpose of civil laws is precisely to “limit the freedom individuals" 77. This question clearly reveals the main meaning of Hobbes's distinction between right (natural) and law (civil, positive). “For right,” Hobbes emphasizes, “is freedom, precisely the freedom that civil law leaves us. Civil law is an obligation and takes away from us the freedom that natural law provides us. Nature grants every person the right to ensure his safety with his own physical strength and, in order to prevent an attack on himself, to attack any suspicious neighbor. Civil law deprives us of this freedom in all those cases where the protection of the law ensures safety.”78.

Moreover, this is the case in all forms of state: freedom is the same in both monarchy and democracy. From these positions, Hobbes sharply reproaches the ancient authors (especially Aristotle and Cicero), who linked freedom with a democratic form of government. To these views he attributes dangerous and destructive consequences: “And through the reading of Greek and Latin authors, people from childhood acquired the habit of favoring (under the false mask of freedom) the rebellions and dissolute control of their sovereigns, and then the control of these controllers, as a result of which so much blood was shed, that I consider myself entitled to assert that nothing has ever been bought at such a high price as the study of Greek and Latin by Western countries” 7E.

When characterizing civil laws, Hobbes emphasizes that only the sovereign is in all states

ties by the legislator, and the freedom of the sovereign is supra-legal in nature: the sovereign (one person or assembly) is not subject to civil laws.

Regarding the question of customs, he notes that the basis for recognizing the force of law behind a long practice is not the length of time, but the will of the sovereign (his tacit consent). From these positions, he objects to lawyers who consider only reasonable customs to be law and propose to abolish bad customs. Deciding what is reasonable and what is subject to abolition, Hobbes notes, is a matter for the legislator himself, and not for jurisprudence or judges. The law must correspond to reason, but precisely to the reason of the sovereign.

With regard to laws established under previous sovereigns, but continuing to operate under the present sovereign, Hobbes formulates the following rule: the legislator is not the one by whose power the law was first issued, but the one by whose will it continues to remain law. “The legal force of the law,” he emphasizes, “consists only in the fact that it is an order of the sovereign” 8°.

An essential feature of civil laws, according to Hobbes, is that they are brought to the attention of all those who are obliged to obey them, through oral or written publication or in another form, obviously emanating from the supreme power.

The interpretation of all laws (both civil and natural) is the prerogative of the supreme power, therefore only those who are entrusted with this by the sovereign can interpret them.

Only with the establishment of the state do natural (moral) laws become actual laws (“orders of the state”, “civil laws”), due to the fact that the supreme power obliges people to obey them. Taking this into account, Hobbes says that “natural and civil laws coincide in content and have the same scope”, that “natural law is in all states of the world part of civil law, and the latter, in turn, is part of the dictates of nature”81. Further, he explains that civil and natural laws are “not various types, A various parts rights,

80 Ibid., p. 214.

81 Ibid., p. 209.

of which one, the written part, is called civil, the other, unwritten, is called natural law”82. Obedience to civil law is one of the requirements of natural law.

In general, Hobbes gives the following definition of civil law: “Civil law is for every subject those rules which the state, orally, in writing, or by other sufficiently clear signs of its will, has prescribed to him, so that he may use them to distinguish between right and wrong, i.e. . that is, between what is consistent and what is not consistent with the rule" 83.

Among civil laws (i.e., positive human laws), Hobbes distinguishes distributive and criminal laws84. Distribution laws are addressed to all subjects and define their rights, indicating the ways of acquiring and maintaining property, the procedure for claims, etc. We are essentially talking about issues of private law (substantive and procedural).

Criminal laws, according to Hobbes, are addressed to officials and determine punishments for violations of laws. Although every person should be informed in advance about these punishments, the command here, according to Hobbes, is not addressed to the criminal, who cannot be expected to honestly punish himself.

In addition, he divides laws into fundamental and non-fundamental. "He includes fundamental laws that oblige subjects to support the power of the sovereign, without which the state will perish. Here Hobbes includes laws on pre-

82 Ibid., p. 210. Therefore, current customs as non-written

Hobbes considers this law to be a natural law (i.e., not a positive

tive, not civil law). However, these contradictions

in Hobbes's judgments are not removed, because he repeatedly

recognizes the possibility of an oral form of civil law,

in light of which the latter cannot be characterized as

the “written part” of all laws. By the way, Hobbes should have

talk about natural and civil laws as different

certain parts of laws (legislation), and not law, since

law in his teaching (as opposed to law) is only a natural

civil law, moreover, interpreted by him as a subjective right

nom, and not in the objective sense.

83 Ibid., p. 208.

" Ibid., pp. 221-222. 85 Ibid., p. 224.

Rogayvah of the Supreme Power (law of war and peace, administration of justice, appointment officials and in general the right of the sovereign to do whatever he deems necessary in the interests of the state). Non-fundamental laws include laws (for example, on litigation between subjects), the abolition of which does not entail the collapse of the state.

Along with civil laws (as distinguished from natural laws), Hobbes also identifies divine laws - the commandments of God, addressed to a certain people or certain individuals and declared as laws by those who were authorized by God to do so.

The rationalism of Hobbes's approach to divine laws is clearly manifested in the fact that he recognizes them only to the extent that they do not contradict natural laws; Only in this sense and scope do they have mandatory significance. As if compensating for his rationalistic reduction of theonomial rules to rational ones, Hobbes readily recognizes the divine nature of natural laws, but this does not change the essence of the matter - their autonomous rationalistic meaning.

The secular, anti-theological orientation of Hobbes’s position that “faith and the secret thoughts of man are not subject to command” is also obvious. 86 This means that faith in general (including faith in divine laws) is not the object of legislative regulation.

But, as they say, a holy place is never empty, and Hobbes - in striking accordance with this proverb - puts the state ("mortal god", Leviathan) in the place of the "immortal god" as a legislator. “I therefore conclude,” he writes, “that in all things not contrary to the moral law (i.e., natural law), all subjects are obliged to obey, as divine laws, what is declared to be such state laws» 87.

Legislation, therefore, becomes a tool for implementing important spiritual and ideological attitudes and views. This, however, also follows from Hobbes’s judgments about management, control and prices.

88 Ibid., p. 223.

87 Ibid., p. 223-224.

the sovereign's powers regarding scientific doctrines and public opinion.

Based on the fact that “men’s actions are determined by their opinions”88, Hobbes sees the good management of opinions as the way to good management of people’s actions in order to establish “peace and harmony” among them. And although he notes that he recognizes the truth as the only criterion for the suitability or unsuitability of a particular teaching, he believes that this is not contradicted by the verification of this teaching from the standpoint of “the affairs of the world,” which in his use of words means, in fact, the highest, absolutely uncontrolled statist interests.

Thus, he believes that “it is the competence of the supreme power to be the judge of which opinions and teachings hinder and which contribute to the establishment of peace, and, therefore, in what cases, within what limits and to what people the right to make speeches can be granted to the mass of the people and who should examine the doctrines of all books before publishing them” 8E. People who are ready to take up arms to defend and implement this or that opinion are in a state of suspended hostilities, in a state of discord and continuous preparation for civil war. Hobbes resolves this struggle of opinions and teachings with the help of censorship - “judges of opinions and teachings” 90 appointed by the sovereign.

The anti-democratic, anti-liberal and anti-individualistic character of Hobbes's concept of sovereignty is obvious. Its essential consequence is the interpretation of law (all positive human legislation) as an order of the sovereign. Moreover, the law (civil, state) and law (natural) are contrasted in such a way that the law summarizes only the lack of freedom, lack of rights and duties of subjects in relation to the sovereign and the freedom, sovereignty and powers of the sovereign in relation to subjects.

Freedom in Hobbes's interpretation is a synonym for the natural nature he criticizes (in relation to individuals).

88 Ibid., p. 150-151. French materialists and educators

Then they will say that the world is ruled by opinions.

89 Ibid., p. 150.

90 Ibid., p. 151.

rights and evidence of the state of war of all against all. Taking into account the fact that with the establishment of the state, the natural rights and freedoms of the subjects pass to the sovereign, who thus turns out to be the only real bearer of freedom and right, we can say with complete confidence that even in the state of statehood constructed by Hobbes, the peace he sought was not achieved and the war continues. Only its front and character have changed: instead of a war of all against all (and along with its insurmountable remnants), a war (internal and external) is unfolding, the source of which is the law and freedom (in the sense of the Hobbesian concept - natural) of the sovereign.

Hobbes himself recognizes the natural-legal (and, therefore, military) nature of the relationships between various sovereigns (and sovereign states). Consequently, in this regard, the establishment of civil power leads to a transition from sporadic and chaotic small (individual and group) skirmishes to organized (at the national level and scale) war between sovereigns.

Paralyzed by the fear of revolution and civil war and busy searching for internal harmony, Hobbes, in fact, completely loses sight of the problems of peace and war between states. Everywhere by "peace" he means inner world, namely the state of obedience of subjects to authorities. But even here, in the sphere of the Hobbesian construction of the civil state, overcoming war and achieving peace is very illusory, since the free sovereign in his relations with unfree subjects is essentially (and according to the specific natural-legal meaning of Hobbes’s interpretation of freedom) in a state of nature (not bound by anything). , has the right to everything, etc.).

The dialectic of the process of contractual establishment of the state depicted by Hobbes is, therefore, such that the exit of people from the state of nature is accompanied by the price of such a renunciation of their rights and freedoms in favor of civil power that the latter, taking into its hands the powers and possibilities of the state of nature, turns into a new and unique subject of natural law and freedom. This exclusivity of power as a subject of natural law in a civil state is the essence of sovereignty in Hobbes.

sky interpretation and the meaning of his understanding of positive law as an order of the sovereign.

This legal understanding, based on the statist concept (uncontrolled freedom of the state, sovereign, civil power in general), makes Hobbes the founder of bourgeois legal positivism. Leading representatives of this trend (J. Austin, S. Amos, K. Gerber, P. Laband, G. F. Shershenevich, etc.) accept and defend (in one modification or variation) the basic idea of Hobbes’s interpretation: positive law ( Hobbes has a positive law) - this is the order of the sovereign.

Thus, J. Austin characterized law as “a set of rules established by a political leader or sovereign” and emphasized: “Every law is a command, an order”91. Likewise, according to S. Amos, “law is an order from the supreme political power of the state in order to control the actions of individuals in a given community”92. G. F. Shershenevich held similar views. “Every rule of law,” he wrote, “is an order” °3. Law, in his assessment, is “the product of the state,” and state power is characterized by him as “that initial fact from which the norms of law proceed, clinging to each other” 94.

The main difference in the approaches of Hobbes and the above-mentioned positivists to law is that Hobbes, while admitting a state of nature, recognizes natural law within its framework, while his followers deny both. But Hobbes, as we have seen, denies natural law (though only among subjects) in the civil state.

The essential commonality in their positions is that under statehood, only positive law (positive law), understood as an authoritative order, is recognized as law. Denial of content

91 Austin J. Lectures on Jurisprudence or the Philosophy of Positive Law. L., 1873, vol. 1, p. 89, 98.

For a detailed critical analysis of these and other similar provisions of J. Austin, as well as Sh. Amos, G. F. Shershenevich and a number of other positivists, see: Zorkin V. D. Positivist theory of law in Russia. M., 1978, p. 60 et seq.

p Amos Sh. A systematic View of the Science of Jurisprudence. L, 1872, p. 73.

93 Shershenevich G. F. General theory of law. M., 1910, issue. 1, p. 281.

»4 Ibid., p. 314.

(including value-substantive) features of law is accompanied by a substitution of the legal properties of the law (and the so-called positive law in general), its power source and character. By its order, state power generates law - this is the credo of this type of legal understanding, the true essence of which is manifested in the statement: everything that state power orders is right (law). The difference between law and arbitrariness is thereby, in principle, deprived of an objective and meaningful meaning and for adherents of the legal-positivist approach has only a subjective and formal character: obvious arbitrariness, sanctioned by a certain subject (state) in a certain form (in the form of a particular act - a law, a rescript , decree, etc.) is unconditionally recognized by law.

Legal positivism thereby underlines its complete helplessness to establish any scientifically significant objective criteria for distinguishing law as a special social phenomenon from other phenomena (both from arbitrariness and lawlessness, and, say, from morality) and is limited to pointing to the authority of power as the only criterion for this difference. In the positivist interpretation, magical possibilities are recognized behind the order of state power. It turns out that the order solves problems not only of a subjective nature (formulation of legal norms), but also of an objective nature (formation, creation of the law itself), as well as the actual scientific profile (establishing and clarifying the difference between law and arbitrariness and non-legal phenomena in general). In all this, the statist roots and attitudes of legal-positivist views are clearly manifested.

The Renaissance can rightfully be considered a new stage in the development of social thought. During this period, new research aimed at studying various aspects of society appeared, which can certainly be attributed to the field of sociology. Erasmus of Rotterdam, Thomas More, Niccolo Machiavelli, Michel Montaigne - this is not a complete list of great medieval scientists who raised problems of human relations in society. As a result, a model of society began to emerge that resembled a community, where order and moral principles were regulated by the will of God and traditions. Man played a very insignificant role in such a system of the universe.

Later, figures of the Enlightenment radically changed their view of society and the place of man in it. Scientists study the structure of society, determine the origins of the development of inequality, the emergence of heterogeneity in society, and identify the role of religion in social processes.

Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527) turned to the ideas of Plato and Aristotle and created on their basis an original theory of society and state.

His main work, “The Prince,” describes the principles of creating a strong state in conditions where civic virtues are not developed among the people, but the emphasis is not on the structure of society, but on the behavior of the political leader. Machiavelli formulated the laws of behavior for a ruler who wants to achieve success.

Law One: People's actions are governed by ambition and the desire for power. To achieve social stability, you need to find out what social layer more ambitious: those who want to keep what they have, or those who want to acquire what they do not have. Both motives are equally destructive for the state, and any cruelty is justified to maintain stability.

Law two: a smart ruler should not keep all his promises. After all, subjects are not in a hurry to fulfill their obligations. When seeking power, you can waste promises, but when you get there, you don’t have to fulfill them, otherwise you will become dependent on your subordinates. It is just as easy to earn hatred for good deeds as for evil ones, but evil is a sign of firmness. Hence the advice: to gain power, you must be kind, but to retain it, you must be cruel.

Law three: evil must be done immediately, and goodness must be done gradually. People value rewards when they are rare, but punishments must be carried out immediately and in large doses.

Thomas Hobbes(1588-1679) took the next step: he developed the theory of the social contract, which became the basis for the doctrine of civil society. Hobbes posed the question: “How is society possible?” - and answered it like this: firstly, people are born incapable of social life, but acquire an inclination towards it as a result of upbringing (socialization); secondly, civil society is generated by the fear of some of others. The natural state of people, according to Hobbes, is a “war of all against all,” absolute competition between individuals in the struggle for existence. This natural state of society causes people to fear each other. It is fear that forces people to create a civil society, i.e. a society that, on a contractual basis, guarantees to each of its members relative security from the hostile actions of others. Fear does not separate, but on the contrary, connects, motivates us to care about everyone’s safety. State - best way satisfy such a need.

Civil society is the highest stage of development; it rests on legal norms accepted by all. In civil society, three forms of government are possible: democracy, aristocracy, monarchy. As a result of the social contract, the war of all against all ends: citizens voluntarily limit personal freedom, receiving reliable protection in return.

During this period, the Italian philosopher Giambattista Vico(1668-1744) tried to create the basis of a new science of society, to develop a scheme for the “movement of nations.” This attempt was the only one left at that time. Basically, all research in this area was characterized by fragmentation and unsystematicity, and therefore it is impossible to say about the emergence of sociology as a science at that time. Analysis of society, human behavior in a group, issues of heterogeneity and inequality did not attract sufficient attention from researchers, and achievements in the field of studying social phenomena were insignificant compared with successes in other areas of scientific activity.

Giambattista Vico(1668-1744) during the Enlightenment, he developed the principles of historical method and knowledge of the “civil world”, completely created by people. According to Vico, the origin of all public institutions should be sought in the “modifications of consciousness” of people, and not in any external force that controls people like puppets. Moreover, social order arises and develops “naturally... under certain circumstances of human necessity or benefit.” Since history and the civil world are completely created by people according to their understanding, they are subject to systematization, and if an appropriate method is created, history can be turned into a science no less accurate than geometry. Vico proposed a number of rules: if periods in history are identical, then one can talk about the analogy of one period to another, but one should not extend ideas and categories of modernity to individual eras; similar periods alternate in approximately the same order; history moves in a spiral, not in a circle, entering the traditional phase in a new form (the law of cyclical evolution). Emphasizing the specificity of historical eras, Vico sees the unity of world history, strives to find the common, repeating and essential in history different nations and countries. Each society undergoes an evolutionary cycle, consisting of three successively replacing each other stages (“age of gods”, “age of heroes” and “age of people”) and ending with the crisis and death of this society. The specifics of the “internal” history of each era depend on the characteristics of “mores” (by which Vico understands not only the moral and traditional way of life of a nation, but also the economic one), legal institutions, forms of government and methods of legitimizing power, interpersonal communication and characteristic stereotypes of thinking. These factors manifest themselves in the concrete eventual flow of history as the “struggle of classes” and the dynamic logic of socio-political forms of social life corresponding to its vicissitudes. Fixing the state of contemporary European nations in the phase of the “century of men” (“civil age”), Vico discovers the main impetus of historical changes in the confrontation between the plebeians and the aristocracy. Their struggle (the plebeians strive to change the social organization, the aristocrats to preserve it) leads to a consistent change in power-organizing forms from aristocracy through democracy to monarchy. The decomposition of the monarchy is accompanied by the decomposition of the entire social organism and the destruction of civilization. The historical cycle resumes, starting again from the religious stage of development. But there is no absolute repetition in history and there will not be, since there is freedom of human decision. If the specific events of the cyclical “movement of nations” may differ, then the very law of cyclical reproduction of the essential forms of cultural and historical entities is unified and universal, supporting the thesis that was important for Vico about the “return of human things” (later rooted in the philosophy of F. Nietzsche and O. Spengler ).

Sociology has its roots in the Age of Enlightenment and historical events French Revolution, which had a significant impact on further development humanity. Here we should name such thinkers as Vico (1668-1744), Montesquieu (1689-1755), Voltaire (1694-1778), Rousseau (1712-1778), Helvetius (1715-1771), Turgot (1727-1781), Condorcet (1743-1794).

Later, figures of the Enlightenment radically changed their view of society and the place of man in it. Claude Adrian Helvetius, Denis Diderot, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Voltaire began to analyze the structure of society, determine the sources of the development of inequality, the emergence of heterogeneity in society, and identify the role of religion in social processes. Having created a mechanical, rational model of society, they identified the individual as an independent subject, whose behavior depends mainly on his own volitional efforts.

Charles Louis Montesquieu (1689-1755). He played a special role in creating the ideological and theoretical basis of sociological science. The main work “On the spirit of laws.” He sets out to understand history, to see a certain order in the multitude of customs, morals, habits, ideas, and various socio-political institutions. Behind a chain of events that seem random, he tries to see the patterns to which these events are subject. Many things, he noted, govern people: climate, religion, laws, principles of government, examples of the past, morals, customs; as a result of this, a common spirit of the people is formed.

In his works, Montesquieu paid special attention to political and state institutions. Of particular interest are his ideas about the separation of powers and three types of government (democracy, aristocracy, despotism), which were subsequently used as the basis for the political structure of modern bourgeois-democratic states.

The emergence of the theory of geographical determinism is largely associated with the name of Montesquieu. He studied the influence of climate, geographical environment, population size on various aspects of socio-political and economic life. In his opinion, the nature of the political regime depends on the size of the territory occupied by the state. For example, Montesquieu believed that a republic by its nature requires a small territory, a monarchical state must be of medium size, and the vast size of an empire is a prerequisite for despotic rule.

Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778). He developed the concept of “ordre naturel” (natural order), which, thanks to the social contract, turns into “ordre positif” (“positive order”).

Unlike Hobbes, Rousseau does not believe that people are naturally hostile to each other. In his understanding, man is by nature good, free and self-sufficient.

The primitive state of human society is characterized by freedom and equality for all. The period of emergence from the state of savagery, when a person becomes a social being, seemed to him the happiest era - the “golden age”.

Further ills of humanity arise as social inequality increases. As a result of the division of labor, everything is appropriated by a few, who enter into a social contract with the poor, based on the inequality and lack of freedom of the poor.

This is how inequality is fixed with the help of a contract. It can only be eliminated by transferring the rights of all individuals to society through a voting process where the interests individuals are neutralized and the general will is justified. In this social contract, the position of people is twofold: on the one hand, they are independent as parts of the sovereign, and on the other, as subjects they are forced to submit to the general will. Rousseau substantiates the legality of the revolutionary coup: the people have the right to “throw off the yoke” and “regain their freedom,” since slavery is contrary to the very nature of man. The basis of Rousseau's political theory is the doctrine of popular sovereignty as the implementation of the general will. It, in turn, acts as a source of laws, a measure of justice and the main principle of management.

Hobbes begins his research by finding out what a person is, what his essence is. Hobbes presents man in two forms - as a natural individual and as a member of a community - a citizen. A person can be in a natural or social (civil, state) state. Hobbes does not directly say that there are two types of morality, but he does talk about morality and the concepts of good and evil in connection with the state of nature and in connection with the civil state, and he shows that the differences between his characteristics of morality are significantly different. What characterizes the natural state? - This is a state in which the natural equality of people is manifested. Of course, Hobbes cannot help but see individual differences, both physical and mental; however in total mass these differences are not so significant that it is impossible in principle to talk about the equality of people. Equality of ability gives rise to equality of hope for achieving goals. However, limited resources do not allow everyone to satisfy their needs equally. This is where rivalry between people arises. Constant rivalry breeds mistrust between them. No one, having something, can be sure that his property and he himself will not become the subject of someone else's militant claims. As a result, people experience fear and hostility towards each other. To ensure his own security, everyone strives to strengthen his power and strength and to ensure that others value him the way he values himself. At the same time, no one wants to show respect to another, lest the latter be taken as an expression of weakness.

All these features of human life in the state of nature, namely: rivalry, distrust and thirst for glory, turn out to be the cause of the constant war of all against all. Hobbes interprets war in the broad sense of the word - as the absence of any guarantees of security; war "is not only a battle, or military action, but a period of time during which the will to fight through battle is clearly evident."

In the natural state, relations between people are expressed in the formula: “man is a wolf to man.” Citing this formula, Hobbes emphasizes that it characterizes relations between states, in contrast to another - “man is God to man,” which characterizes relations between citizens within a state. However, as one can judge from " Human nature", where Hobbes represents all human passions through the allegory of a race, both in the social and in the state of nature, the principle of "man is a wolf to man" is always present in relations between people to the extent that mistrust and malice are the motives of human actions. The state of nature as a state of war is characterized by one more feature: there are no concepts of fair and unfair - “where there is no common power, there is no law, and where there is no law, there is no injustice.” Justice is not a natural quality of man, it is a virtue. which is affirmed by people themselves in the process of their self-organization. Laws and agreements are the actual basis (“reason,” as Hobbes sometimes says) for the distinction between justice and injustice. In the state of nature, there is generally “nothing generally binding, and everyone can do what he personally sees fit. good." In such a state, people act on the principle of liking or not liking, wanting or not wanting; and their personal inclinations turn out to be the real measure of good and evil.

Natural law. In the state of nature, the so-called natural law (right of nature, jus naturale) operates. Hobbes insists on separating the concepts of “right,” which simply means freedom of choice, and “law,” which means the need to act in a certain established way. The law thereby indicates an obligation; freedom is on the other side of obligation. Obviously, this is not a liberal understanding of freedom, right and obligation. Natural law, according to Hobbes, is expressed in “the freedom of every man to use his own powers at his own discretion for the preservation of his own nature, that is, his own life.” According to natural law, everyone acts in accordance with their desires and everyone decides for themselves what is right and what is wrong. "Nature has given everyone the right to everything." According to Hobbes, people are born absolutely equal and free, and in natural state everyone has the right to everything. Therefore, the state of nature is defined as “a war of all against all.” After all, if every person has the right to everything, and the abundance around us is limited, then the rights of one person will inevitably collide with the same rights of another.

The state is opposed to the state of nature (civil status), the transition to which is determined by the instinct of self-preservation and a reasonable desire for peace. The desire for peace, according to Hobbes, is the main natural law.

Only force can transform natural laws into imperatives, i.e. state. The state arises in two ways: as a result of violence and as a result of a social contract. Hobbes gives preference to the contractual origin of the state, calling such states political. By concluding a social contract among themselves, people alienate all their natural rights in favor of the sovereign. Hobbes considers it possible to draw an analogy between the state and a machine, an “artificial body” that is created by man to preserve his life. The state is, according to Hobbes, a “mechanical monster” with extraordinary and terrible power: it can protect the interests of a person, the interests of parties and a large social group.

Hobbes views the state as the result of a contract between people, putting an end to the natural pre-state state of “war of all against all.” He adhered to the principle of the original equality of people. Individual citizens voluntarily limited their rights and freedom in favor of the state, whose task is to ensure peace and security. Hobbes extols the role of the state, which he recognizes as the absolute sovereign. On the question of the forms of the state, Hobbes' sympathies are on the side of the monarchy. Defending the need to subordinate the church to the state, he considered it necessary to preserve religion as an instrument of state power to curb the people.

Hobbes believed that the very life of a person, his well-being, strength, and rationality depend on the activities of the state political life society, the common good of people, their consent, which constitutes the condition and “health of the state”; its absence leads to “disease of the state”, civil wars or even the death of the state. From this Hobbes concludes that all people are interested in a perfect state. According to Hobbes, the state arose as a result of a social contract, an agreement, but, having arisen, it separated from society and is subject to the collective opinion and will of the people, having an absolute character. The concepts of good and evil are distinguished only by the state, but a person must submit to the will of the state and recognize as bad what the state recognizes as bad. At the same time, the state must take care of the interests and happiness of the people. The state is called upon to protect citizens from external enemies and maintain internal order; it should give citizens the opportunity to increase their wealth, but within limits that are safe for the state.